It seems that my choreographic voice has been shaped by re-turns — not as repetitions, but as re-encounters that offer new perspectives. Etymologically, returning suggests going back (re) and turning again — a motion that, in dance, evokes spirals, shifts in direction, and circular movements that never arrive at the same place twice. To re-turn is to be in motion, to revisit while being changed, to see again with different eyes and a different body. Over time, I’ve come to notice that each return — to a place, a memory, a body of work — reveals something new and gives me strength. The movement of re-turning allows me to gather myself differently, to see anew what once seemed familiar.

During my master’s studies in dance pedagogy, as I transitioned into choreography and dance pedagogy, I realized that returning to my own dance trajectory was a crucial part of the process. Because I hadn’t trained in just one specific dance style or under a single master, I often felt uncertain about what I had to pass on. It seemed, at times, that I was fragmented — that I had no clear lineage to offer.

But by returning to those diverse experiences, I began to understand that it wasn’t about remembering each technique or style. Rather, it was about recognizing the tools I had developed along the way — tools that enabled me to move between different vocabularies and embody multiple perspectives, even if I hadn’t always been consciously aware of them. These tools only began to take shape through the act of returning. And I’ve come to see them not as fixed methods, but as openings — flexible, responsive, and continually transforming.

This approach stands in tension with what the dance market often demands: a defined method, a singular artistic voice. Yet what returning to my own practice has taught me is that dance holds a powerful potential — not to define, but to facilitate encounters. It creates shared spaces where difference can meet. That, to me, is the real strength of dance: to make space for exchange, for multiplicity, and for what might emerge in-between.One such re-turn marked my first professional commission: the piece Wohin? (Where to?), created for the Balé de Rio Preto (City Ballet of Rio Preto). It was a homecoming — artistically and geographically — after many years abroad. Influenced by Guy Debord’s reflections on spectacle and dérive, the piece explored cycles, impermanence, and transformation. These were the questions that animated the work. It became a moment of re-sharing, of learning alongside a new generation of dancers in the city where I was formed.

“I return to the studio where I once danced. It welcomes me like a memory with dust on it — familiar but not unchanged. My body knows the floor, but my gestures no longer ask for permission.”

That same impulse of re-turn shaped my piece Lampejos: Uma Degustação Visual (Flashes: A Visual Tasting), created for Cisne Negro Cia de Dança in 2022 — the company where I danced for seven years, where many of my most meaningful friendships were born in a studio in Vila Madalena. Cisne Negro was once my dream company. Re-turning there — not as a dancer, but as a choreographer — was a full-circle moment.

The spark for Lampejos came in Paris, in the home of composer Jean-Jacques Lemêtre. Among his vast collection of instruments, a berrante — a curved horn — caught my attention. Its sound transported me to my childhood in São José do Rio Preto. That singular sound asked: Can a body re-turn to a memory through vibration alone?

We followed that question into the rehearsal room. What returns when nothing is sought? What flickers when memory escapes language? We explored how movement escapes ownership — how it travels between bodies, reverberates, and transforms. Can a gesture begin in one dancer and finish in another? Can silence tremble? Can presence echo?

“I choreograph like someone remembering — never with precision, always with openings. The movements return not as form, but as mood, as texture. They don’t seek closure. They seek presence.”

We moved without counts, guided by breath, attention, and resonance. Jean-Jacques didn’t impose rhythm — he breathed with us, composing landscapes for the body to inhabit. Emotion wasn’t performed; it was displaced, refracted, shared. I brought flashes of my own memories with Cisne Negro into the space — fragments, stories, sensations — and they met the dancers’ own estrangement. What emerged was something between us: trembling, twisting, clashing, floating, dancing.

Re-turning was also the choreographic force in Urutau, a work created for and with the Corpo de Dança do Amazonas, premiered in the majestic Teatro Amazonas in Manaus — a place I had last visited more than twenty years earlier as a young dancer on tour. This return was not only geographic but affective and critical. I reconnected with the city through a different lens: as a choreographer, researcher, and collaborator.

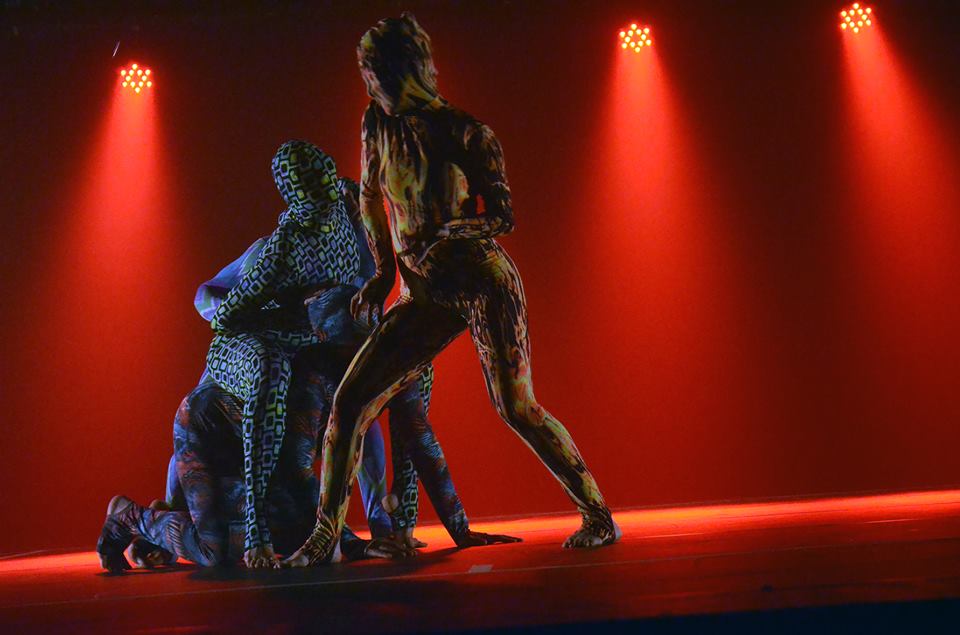

There, I rejoined artists who had shaped me from the beginning — director Mário Nascimento, composer Fábio Cardia, and stage designer Marcelo Zamora. Their passion for dance had once “contaminated” me in the best sense. Now, we could co-create again with deeper listening.

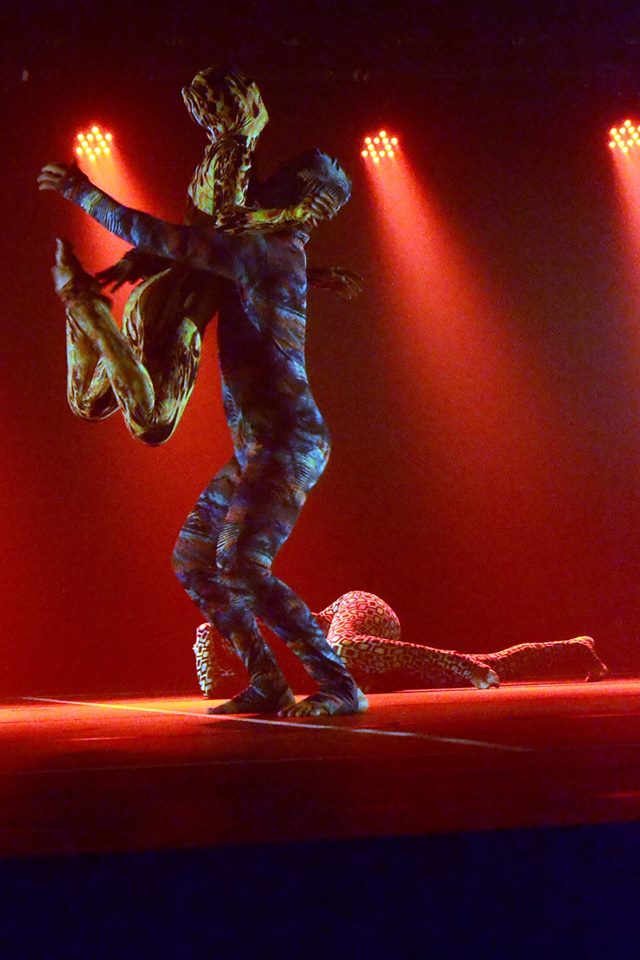

In Urutau, the re-turn also guided the theme: a reflection on the history and haunting logic behind the Teatro Amazonas itself — a monument of rubber wealth and colonial fantasy. Through choreography, I sought to undo the logic of spectacle and extraction, to unearth the invisible histories and resistances that vibrate beneath its grandeur.

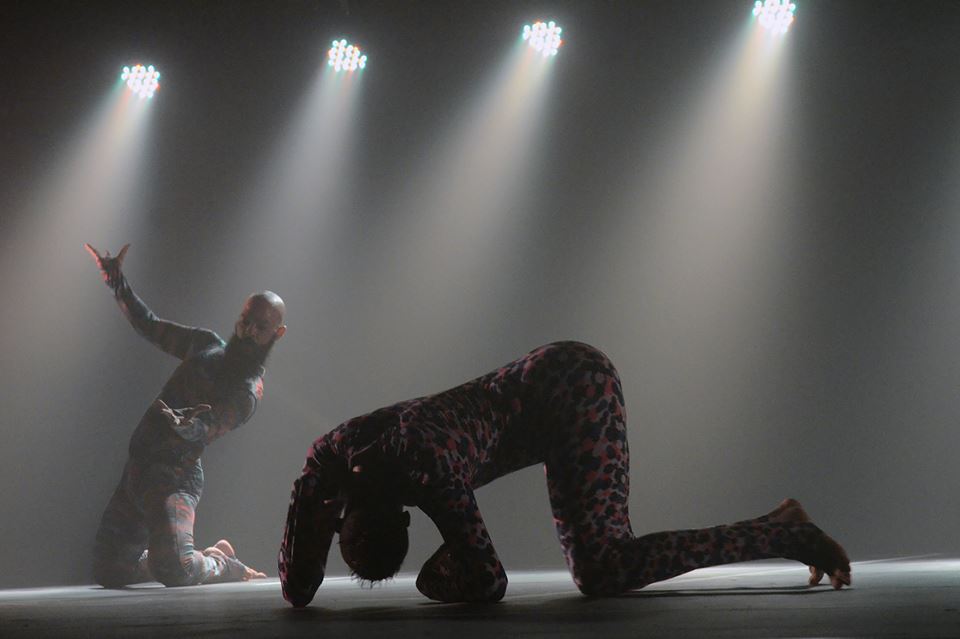

Through the process and movement research, the qualities of the bird urutau started to emerge — its camouflage, its nostalgia, and its stillness as a form of resistance and survival mechanism. We thought of the body as a landscape, off-balance and trembling. The movement became a slow implosion, a soft undoing of the “illusion of Faust,” as Edineia Mascarenhas puts it — the fantasy of endless gain. Instead, we danced toward a logic of deceleration.

“To return to the Amazon was to re-enchant — with wonder and reverence for the land, its histories, and the people who continue to care for it despite centuries of violence and extraction. It was also to listen again — through the noise, through what has been silenced, displaced, or rendered invisible. This return was not a homecoming; it was a reckoning. I arrived with new awareness, new questions, and a deepened sense of responsibility. In that context, re-enchantment became a political and poetic act — one that allowed Indigenous presences, gestures, and cosmologies to reflorestar my choreographic thinking. Their ways of inhabiting the world invited me to see movement differently, to feel time differently, to open myself to practices of care, relation, and transformation.“

In 2023, I returned once more to my hometown to create Aquilo que me Move, a collaboration with dancer Zilda Arali. The piece centered on the aging body in dance, capturing Zilda’s powerful presence and emotional depth as she stood on stage at the age of sixty. After a lifetime dedicated to dance — and following an illness that left her unable to walk for nine months — Zilda continues to embrace movement as a means of transformation.

The entire creative process emerged from her personal and professional archives, which we approached not as static or nostalgic records, but as living materials with generative potential. In this piece, memory was not fixed — it trembled, shifted, and returned differently. Working with Zilda deepened my understanding of how archives can live in the body, and how re-turning can become a methodology. It was during this process that the movement of returning began to take shape more consciously in my choreographic practice — not only as an affect or theme, but as a turn toward the archive as a creative force.

Furthermore, engaging with Zilda’s personal archive allowed for a return to a part of Brazilian dance history that exists outside of the major cultural centers. It also offered a way to trace the layered histories of migration in our hometown, São José do Rio Preto.

Each of these works — and the many in between — emerged in contexts of return. I didn’t set out to make choreography about returning, but I found myself moving back: to places, to people, to questions that shaped me. These re-turnings were never nostalgic escapes; they confronted me with change — in myself, in others, in the world. And they left traces on the choreography: in its roughness, its openings, its resistance to closure. Along the way, I began to see how my own habits as a choreographer — what I carry into each process, what I choose to see or not see — could be questioned. What do we inherit when we return? What do we carry into a place, and what do we take from it? What are we asking the dancers to embody — and at what cost? These are not abstract questions. They come with breath, with bodies, with responsibility.